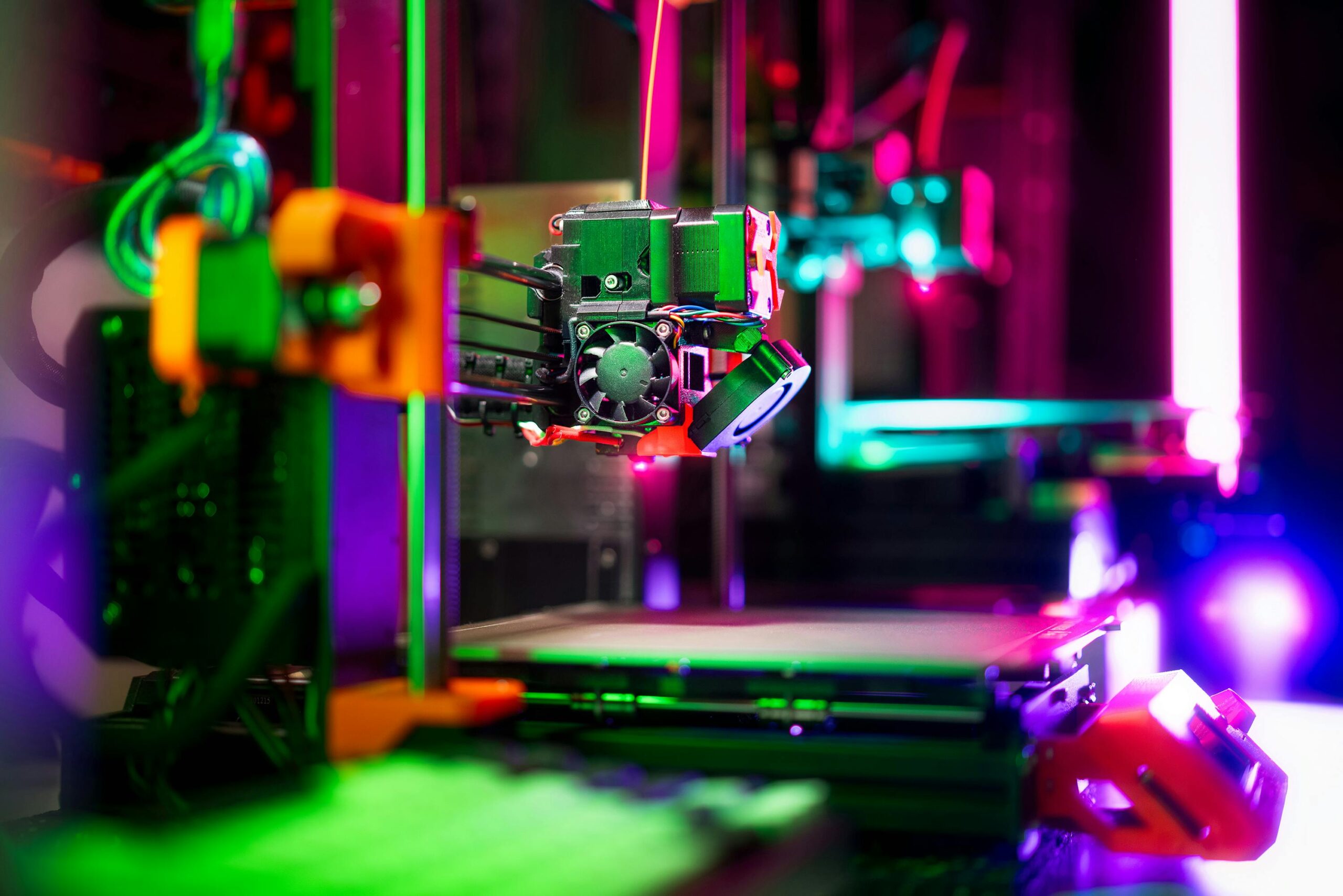

3D printing is transforming manufacturing, but sustainability remains a pressing concern. Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) offers a powerful framework to measure and optimize the environmental impact of additive manufacturing from cradle to grave.

🌍 Understanding Lifecycle Assessment in Additive Manufacturing

Lifecycle Assessment represents a comprehensive methodology for evaluating the environmental footprint of products throughout their entire existence. For 3D printed products, this holistic approach examines every phase from raw material extraction through production, distribution, use, and eventual disposal or recycling. The complexity of additive manufacturing makes LCA particularly valuable, as traditional environmental assessments often overlook the nuanced advantages and challenges specific to 3D printing technologies.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) defines LCA through standards 14040 and 14044, providing a structured framework that ensures consistency and comparability across different studies. When applied to 3D printed products, this standardized approach enables manufacturers, designers, and consumers to make informed decisions based on quantifiable environmental data rather than assumptions or marketing claims.

Breaking Down the Four Phases of LCA for 3D Printing

Goal and Scope Definition: Setting the Foundation

The initial phase establishes the boundaries and objectives of the assessment. For 3D printed products, this involves defining whether you’re comparing additive manufacturing against traditional production methods, evaluating different 3D printing technologies, or assessing material alternatives. The functional unit—perhaps a single component, a complete assembly, or a service delivered over a specific timeframe—must be clearly identified to ensure meaningful comparisons.

System boundaries determine which processes are included in the analysis. A cradle-to-gate assessment might focus solely on production impacts, while a cradle-to-grave approach encompasses the entire product lifecycle including end-of-life scenarios. For 3D printing, these boundaries can significantly affect results, as additive manufacturing often shifts environmental impacts across lifecycle stages compared to conventional manufacturing.

Inventory Analysis: Quantifying Environmental Flows

This phase involves meticulous data collection on all inputs and outputs associated with the product system. For 3D printed items, inventory analysis tracks material consumption including filaments, resins, or metal powders, along with supporting materials like adhesives, solvents, and cleaning agents. Energy consumption during printing—which varies dramatically between technologies like FDM, SLA, SLS, and metal printing—represents another critical data point.

Transportation impacts, though often reduced with localized 3D printing, still merit consideration. Material waste generation, including support structures, failed prints, and excess powder, must be quantified. The inventory phase also documents emissions to air, water, and soil, alongside any hazardous waste streams associated with post-processing operations like curing, sintering, or surface finishing.

Impact Assessment: Translating Data into Environmental Consequences

The collected inventory data transforms into meaningful environmental impact categories during this phase. Climate change impacts, typically measured in carbon dioxide equivalents, reveal the greenhouse gas footprint of 3D printing operations. Resource depletion assessments evaluate the consumption of non-renewable materials and energy sources, particularly relevant given the specialized materials often required for additive manufacturing.

Human toxicity and ecotoxicity categories examine potential health and environmental hazards from material exposure, chemical emissions, and waste disposal. Eutrophication and acidification potentials capture impacts on aquatic ecosystems and soil quality. For 3D printing, photochemical oxidation from volatile organic compounds released during certain printing processes may represent a significant concern depending on the technology and materials employed.

Interpretation: Extracting Actionable Insights

The final LCA phase synthesizes findings to identify environmental hotspots, compare alternatives, and recommend improvements. For 3D printed products, interpretation often reveals surprising insights—perhaps that material production overshadows printing energy consumption, or that product longevity outweighs initial manufacturing impacts. These insights guide strategic decisions about technology selection, material choices, design modifications, and process optimizations.

♻️ Material Considerations in Sustainable 3D Printing

Material selection profoundly influences the environmental profile of 3D printed products. Conventional thermoplastics like ABS and PLA dominate consumer and professional 3D printing, yet their sustainability credentials differ substantially. PLA, derived from renewable resources like corn starch, offers lower carbon footprints during production compared to petroleum-based alternatives, though its end-of-life options present complications since it requires industrial composting facilities rarely accessible to consumers.

Advanced materials including recycled polymers, bio-based composites, and recyclable engineering plastics increasingly provide sustainable alternatives without compromising performance. Some manufacturers now offer filaments produced from post-consumer waste streams, ocean plastics, or industrial byproducts, directly addressing circular economy principles. Metal 3D printing materials, while energy-intensive to produce, enable lightweight designs that dramatically reduce operational energy consumption in aerospace and automotive applications.

Material efficiency represents another crucial sustainability factor. Traditional subtractive manufacturing often wastes 60-90% of input material, whereas additive manufacturing can achieve material utilization rates exceeding 90%. This inherent efficiency advantage, particularly valuable with expensive or environmentally problematic materials, fundamentally alters the sustainability equation for many applications.

Energy Dynamics: Power Consumption Across Technologies

Energy consumption patterns vary dramatically across 3D printing technologies, making technology selection critical for sustainability objectives. Fused deposition modeling (FDM) typically consumes 50-100 watts during printing, positioning it among the most energy-efficient options for polymers. Stereolithography (SLA) and digital light processing (DLP) systems require additional energy for resin curing and post-processing, though print times may be shorter than FDM for certain geometries.

Selective laser sintering (SLS) demands substantially higher energy inputs, with powder bed heating and laser systems consuming several kilowatts. The technology’s ability to produce functional parts without support structures and its high material utilization partially offset these energy demands. Metal 3D printing technologies, including direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) and electron beam melting (EBM), represent the most energy-intensive additive manufacturing options, yet they enable designs impossible through conventional metalworking with significant downstream efficiency gains.

Operational considerations beyond direct printing energy include heated build chambers, ventilation systems, dehumidification equipment, and post-processing apparatus. For comprehensive LCA, these auxiliary energy demands must be allocated appropriately across produced parts, with capacity utilization significantly affecting per-unit environmental impacts.

🎯 Design Optimization for Lifecycle Performance

Design for additive manufacturing (DfAM) principles intersect with sustainability objectives in powerful ways. Topology optimization algorithms generate organic structures that minimize material usage while maintaining strength requirements, reducing both production impacts and operational energy consumption through lightweighting. Lattice structures and internal geometries impossible with traditional manufacturing deliver material efficiency gains of 30-70% compared to solid designs.

Consolidating assemblies represents another DfAM strategy with sustainability benefits. A single 3D printed component replacing multiple traditionally manufactured parts eliminates fasteners, reduces assembly labor, and minimizes transportation impacts from fewer components. The aerospace industry extensively exploits this advantage, with consolidated brackets and ducts reducing part counts, weight, and fuel consumption simultaneously.

Design for longevity and repairability extends product lifecycles, often representing the most impactful sustainability strategy. 3D printing enables economical small-batch replacement part production, keeping products functional long after original manufacturers discontinue support. Modular designs facilitating component replacement rather than complete product disposal align additive manufacturing capabilities with circular economy principles.

Production Scale and Localization Effects

Lifecycle assessment results for 3D printing vary significantly with production volume. For small batches and customized items, additive manufacturing typically demonstrates superior sustainability profiles compared to traditional manufacturing requiring expensive tooling. The crossover point where conventional manufacturing becomes more efficient depends on specific geometries, materials, and technologies but often occurs between hundreds and thousands of units.

Distributed manufacturing enabled by 3D printing technology transforms logistics and transportation impacts. On-demand production near consumption points eliminates warehousing, reduces inventory waste, and minimizes transportation distances. For replacement parts, medical devices, and customized consumer products, these localization benefits substantially improve overall sustainability metrics compared to centralized manufacturing with global distribution networks.

However, distributed manufacturing also presents challenges. Energy grid carbon intensity varies geographically, meaning identical printing operations generate different climate impacts depending on location. Quality control, material sourcing, and waste management become more complex with distributed production, potentially negating some sustainability advantages without proper systems and oversight.

📊 Comparing 3D Printing Against Traditional Manufacturing

Lifecycle assessment studies comparing additive and subtractive manufacturing reveal context-dependent outcomes rather than universal superiority of either approach. For geometrically complex parts in small quantities, 3D printing consistently demonstrates advantages through eliminated tooling, reduced material waste, and compressed supply chains. A medical implant requiring extensive machining from solid metal billets might generate 90% waste through conventional methods, whereas metal 3D printing achieves near-net shapes with minimal waste.

Conversely, high-volume production of simple geometries often favors traditional manufacturing despite tooling impacts. Injection molding’s per-unit energy and material efficiency at scale can outweigh the overhead of mold production when amortized across thousands or millions of parts. The rapid cycle times of conventional processes also reduce accumulated energy from extended machine operation compared to slower additive manufacturing.

Use-phase impacts frequently dominate lifecycle environmental footprints for many products, particularly in transportation and aerospace applications. When 3D printing enables weight reductions of 20-40% through optimized designs, the cumulative fuel savings over a product’s operational life can vastly exceed any differences in manufacturing impacts. This reality shifts sustainability evaluations toward lifecycle thinking rather than production-focused metrics.

🔄 End-of-Life Strategies for 3D Printed Products

End-of-life scenarios significantly influence lifecycle assessment results, yet this phase receives insufficient attention in additive manufacturing sustainability discussions. Mechanical recycling of thermoplastic 3D printing waste, including failed prints and support structures, offers closed-loop material recovery. Specialized systems now shred and reprocess waste into usable filament, though some material degradation occurs with each cycle, eventually limiting recyclability.

Chemical recycling technologies that depolymerize materials to molecular constituents enable indefinite recycling without quality degradation. While currently limited to specific materials like PLA and nylon, these approaches align perfectly with circular economy principles. The development of recyclable thermoset resins for SLA printing addresses a major sustainability gap, as conventional photopolymers cannot be thermally reprocessed.

Design for disassembly becomes particularly relevant for multi-material 3D printed products. Prints combining different polymers, embedded electronics, or integrated metal components complicate recycling and require thoughtful design enabling material separation. Product-as-a-service models, where manufacturers retain ownership and responsibility for end-of-life management, incentivize recyclability and durability during the design phase.

Quantifying Sustainability: Metrics and Indicators

Effective lifecycle assessment requires appropriate metrics capturing environmental performance across relevant dimensions. Global warming potential measured in CO2 equivalents provides the most recognized climate impact indicator. For 3D printing comparisons, expressing this per kilogram of material processed or per unit of functional performance enables meaningful comparisons across technologies and against alternative manufacturing methods.

Cumulative energy demand quantifies total primary energy consumption throughout the lifecycle, distinguishing renewable and non-renewable sources. Material input per service unit (MIPS) captures resource efficiency by comparing total material throughput against functional output. Circularity indicators assess how effectively materials remain in productive use through recycling, reuse, and remanufacturing.

Water consumption, while less frequently emphasized, matters for certain 3D printing technologies and material production processes. Toxicity indicators, including human health and ecosystem impacts, prove particularly relevant for resin-based printing and metal powder handling. A balanced sustainability assessment considers multiple indicators rather than optimizing for single metrics that may create unintended consequences elsewhere.

🚀 Emerging Technologies Advancing Sustainable 3D Printing

Continuous liquid interface production (CLIP) and other high-speed 3D printing technologies dramatically reduce print times, decreasing energy consumption per part while improving economic viability. Bound metal deposition approaches reduce the energy intensity of metal 3D printing by separating powder deposition from sintering, enabling more efficient thermal processes and standard furnace infrastructure.

Large-format additive manufacturing using pellet extrusion rather than filament substantially reduces material costs and embodied energy from feedstock production. These systems process industrial granules, recycled materials, and even shredded waste plastics directly, supporting circular economy implementation at scale. Construction-scale 3D printing with earth-based and recycled materials promises to transform building sustainability.

In-situ resource utilization for 3D printing, particularly relevant for space applications, demonstrates ultimate sustainability by manufacturing products from locally available materials without terrestrial supply chains. Technologies processing regolith, recycled spacecraft components, or even captured atmospheric gases into feedstocks eliminate transportation impacts while enabling long-duration missions and off-world settlements.

Implementing LCA in Your 3D Printing Operations

Organizations seeking to optimize 3D printing sustainability through lifecycle assessment should begin with goal definition and scope determination aligned with strategic objectives. Whether comparing material alternatives, evaluating process changes, or benchmarking against traditional manufacturing, clear objectives guide meaningful analysis. Engaging stakeholders across design, production, and procurement ensures that insights translate into implementable improvements.

Data collection represents the most resource-intensive phase, requiring systematic documentation of material consumption, energy usage, waste generation, and transportation. Starting with primary data from your operations provides the most accurate foundation, supplemented by industry databases for upstream processes like material production and energy generation. Software tools including SimaPro, GaBi, and openLCA streamline analysis, though simplified approaches using spreadsheets and publicly available data can deliver valuable initial insights.

Iterative improvement cycles treating LCA as an ongoing process rather than one-time study maximize value. Baseline assessments identify current performance and major hotspots, while subsequent analyses evaluate improvement initiatives and track progress toward sustainability targets. Sharing methodologies and findings with industry peers through publications and standards bodies advances collective knowledge while potentially generating competitive advantages through demonstrated sustainability leadership.

Policy, Standards, and Future Directions

Regulatory frameworks increasingly recognize additive manufacturing’s unique characteristics, with emerging standards addressing sustainability assessment, material specifications, and circular economy integration. The European Union’s Ecodesign Directive and Circular Economy Action Plan establish requirements favoring 3D printing’s strengths in material efficiency, product longevity, and spare parts availability. Carbon pricing mechanisms and extended producer responsibility regulations will further incentivize lifecycle optimization.

Industry-specific sustainability standards for 3D printing continue evolving through organizations including ASTM International, ISO, and specialized consortia. Standardized LCA methodologies for additive manufacturing enable consistent environmental claims and prevent greenwashing, supporting informed decision-making by purchasers and policymakers. Material-specific environmental product declarations (EPDs) provide transparent lifecycle data facilitating comparisons and informed material selection.

The convergence of artificial intelligence with lifecycle assessment promises to democratize sophisticated sustainability analysis. Machine learning algorithms trained on extensive LCA databases could provide real-time environmental feedback during design, automatically optimizing geometries, materials, and processes for minimal lifecycle impacts. Digital twins integrating operational data enable continuous sustainability monitoring and improvement throughout product lifecycles, transforming environmental performance from static assessment to dynamic optimization.

💡 Practical Steps Toward Maximum Sustainability

Maximizing sustainability with lifecycle assessment for 3D printed products requires systematic implementation across the value chain. Material selection should prioritize recycled content, bio-based alternatives, and recyclability while maintaining necessary performance characteristics. Conducting material LCAs or consulting environmental product declarations guides informed choices beyond marketing claims and conventional wisdom.

Process optimization targeting energy efficiency includes selecting appropriate technologies for specific applications, maximizing build plate utilization to distribute overhead across more parts, and scheduling production during periods of cleaner grid electricity when feasible. Proper maintenance ensuring optimal equipment performance prevents waste from failed prints while extending equipment lifecycles.

Design integration embedding sustainability considerations from initial concept through detailed engineering delivers the most substantial improvements. Cross-functional collaboration between design, sustainability, and manufacturing teams identifies opportunities for material reduction, design for longevity, and repair facilitation. Quantifying lifecycle impacts of design alternatives using LCA tools makes sustainability tangible and actionable rather than abstract aspiration.

The transformative potential of 3D printing for sustainable manufacturing is undeniable, yet realizing this potential requires rigorous lifecycle thinking. By embracing comprehensive assessment methodologies, leveraging emerging technologies, and implementing systematic improvements, manufacturers can ensure that additive manufacturing delivers on its environmental promise. The journey from start to finish—encompassing material extraction, production, use, and end-of-life—provides the complete picture necessary for maximizing sustainability in 3D printed products.

Toni Santos is a materials researcher and sustainable manufacturing specialist focusing on the development of next-generation biopolymer systems, renewable feedstock cultivation, and the practical innovations driving resource-efficient additive manufacturing. Through an interdisciplinary and science-driven approach, Toni investigates how natural organisms can be transformed into functional materials — across filament chemistry, bio-based composites, and closed-loop production systems. His work is grounded in a fascination with algae not only as lifeforms, but as carriers of industrial potential. From algae filament research to bio-resin development and durable low-energy prints, Toni uncovers the material and engineering pathways through which sustainable practices reshape the future of digital fabrication. With a background in material science and sustainable manufacturing, Toni blends polymer analysis with renewable biomass research to reveal how natural resources can be harnessed to reduce carbon footprint, improve durability, and enable circular production. As the creative mind behind Veltrynox, Toni curates biofilament innovations, low-impact printing methods, and material strategies that advance the ecological integration of 3D printing, biopolymers, and renewable manufacturing systems. His work is a tribute to: The renewable potential of Algae Filament Research and Cultivation The transformative chemistry of Bio-Resin Development and Biocomposites The engineering resilience of Durable Low-Energy Print Systems The sustainable future of Eco-Friendly 3D Printing and Green Manufacturing Whether you're a materials innovator, sustainability engineer, or curious explorer of renewable manufacturing, Toni invites you to discover the transformative power of bio-based materials — one layer, one filament, one sustainable print at a time.