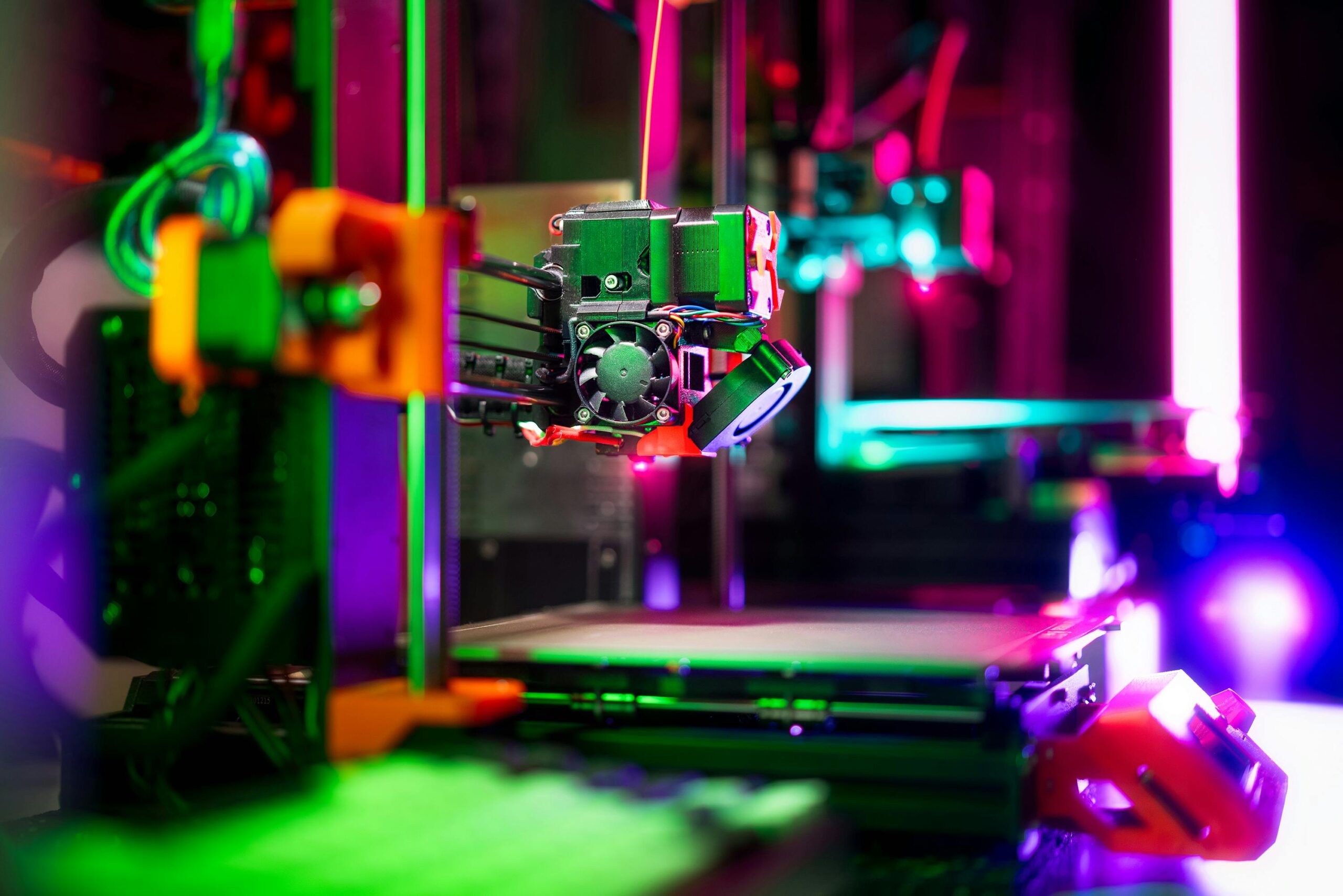

The 3D printing industry faces a growing credibility crisis as environmental claims become more ambitious yet often less substantiated, demanding careful scrutiny from consumers and businesses alike.

🌱 The Green Promise of Additive Manufacturing

Three-dimensional printing has long been heralded as a revolutionary technology with inherent environmental advantages. Compared to traditional subtractive manufacturing methods, additive manufacturing theoretically reduces material waste, enables localized production that cuts transportation emissions, and creates opportunities for circular economy models through recycling and remanufacturing.

However, the reality proves far more nuanced than many marketing materials suggest. As the technology matures and enters mainstream markets, manufacturers and service providers increasingly leverage sustainability messaging to differentiate their offerings. This surge in environmental positioning has inevitably opened the door to greenwashing—the practice of conveying misleading impressions or providing unsubstantiated claims about environmental benefits.

The 3D printing sector’s sustainability narrative deserves critical examination. While legitimate environmental advantages exist, exaggerated or misleading claims undermine consumer trust, distort market competition, and ultimately hinder genuine progress toward sustainable manufacturing practices.

Understanding Greenwashing in the 3D Printing Context

Greenwashing in 3D printing manifests through various tactics, from vague terminology and selective disclosure to outright fabrication of environmental credentials. Companies may emphasize certain green attributes while conveniently omitting problematic aspects of their products or processes.

Common Greenwashing Tactics in Additive Manufacturing

The additive manufacturing industry employs several recurring greenwashing strategies that warrant careful consideration. Hidden trade-offs represent perhaps the most prevalent issue, where companies spotlight one environmental attribute while concealing others. A filament manufacturer might emphasize biodegradability while remaining silent about the energy-intensive production process or the petroleum-based components in their supposedly eco-friendly material.

Vague claims without specificity or third-party verification create another problematic pattern. Terms like “eco-friendly,” “green,” or “sustainable” appear frequently on product packaging and marketing materials without clear definitions, measurable metrics, or independent certification. What exactly makes a 3D printer “environmentally conscious” when the company provides no data on energy consumption, material sourcing, or end-of-life recyclability?

Irrelevant claims also muddy the waters. Some manufacturers promote features that sound environmental but provide minimal actual benefit or are legally required anyway. Advertising that a material is “CFC-free” means little when CFCs have been banned for decades across most applications.

🔍 The Material Reality: Filaments and Resins Under the Microscope

Material selection represents one of the most significant environmental considerations in 3D printing, yet it’s also where greenwashing runs rampant. The industry has witnessed an explosion of supposedly sustainable materials, from bio-based plastics to recycled filaments, each marketed with varying degrees of accuracy regarding their environmental credentials.

The Bioplastic Illusion

Bio-based filaments like PLA (polylactic acid) derived from cornstarch or sugarcane have become synonymous with sustainable 3D printing in consumer consciousness. Marketing materials frequently position these materials as straightforward alternatives to petroleum-based plastics, with companies emphasizing renewable sourcing and biodegradability.

The complete picture proves considerably more complex. While PLA does derive from renewable resources, its production involves significant agricultural inputs, including land use, water consumption, fertilizers, and pesticides. The carbon footprint calculation must account for these upstream impacts, which many manufacturers conveniently exclude from their sustainability claims.

Biodegradability claims require particular scrutiny. PLA will indeed break down under specific conditions—typically in industrial composting facilities with controlled temperature, humidity, and microbial populations. In typical landfill conditions or natural environments, PLA persists for years, functioning essentially as conventional plastic. Yet marketing materials often imply or directly state that PLA prints will simply disappear if discarded, creating false consumer confidence about disposal practices.

Recycled Materials:循環 or Circular Washing?

Filaments manufactured from recycled plastics represent another category rife with misleading claims. Companies proudly announce recycled content percentages without disclosing crucial details about the recycling process, energy requirements, or the resulting material properties and longevity.

Mechanical recycling of plastics—the most common approach for creating recycled filaments—degrades polymer chains with each processing cycle. This means recycled materials typically exhibit inferior mechanical properties compared to virgin materials, potentially limiting applications and product lifespan. When products fail prematurely and require replacement, the net environmental benefit diminishes significantly.

Additionally, many “recycled” filaments contain only a percentage of recycled content blended with virgin material, yet marketing emphasizes the recycled component while downplaying the virgin plastic proportion. A filament advertised as “made from recycled plastic” might contain only 30% recycled content—a material fact often buried in fine print or absent entirely.

Energy Consumption: The Elephant in the Print Room 🐘

Energy use throughout the 3D printing lifecycle represents a critical environmental consideration that frequently receives insufficient attention in sustainability discussions. The focus on material waste reduction, while valid, often obscures the significant energy demands of additive manufacturing processes.

Operational Energy Reality

Three-dimensional printers vary dramatically in energy consumption based on technology type, size, and operational parameters. Fused deposition modeling (FDM) desktop printers generally consume less energy than selective laser sintering (SLS) or stereolithography (SLA) systems, which require powerful lasers or extensive UV curing. Large-format industrial systems naturally demand substantially more energy than desktop units.

However, manufacturers rarely provide transparent, standardized energy consumption data. When specifications do appear, they often list peak power ratings rather than actual energy use during typical print jobs, making meaningful comparisons nearly impossible. This information asymmetry prevents consumers and businesses from making truly informed decisions based on energy efficiency.

The printing process itself represents only part of the energy equation. Post-processing requirements—including support removal, surface finishing, curing, and heat treatment—add substantial energy demands that marketing materials typically ignore. A resin print requiring hours of UV curing and isopropyl alcohol washing involves considerably more energy than the printing process alone.

The Localized Production Myth

Advocates frequently champion 3D printing’s potential for distributed manufacturing, arguing that producing goods near their point of use eliminates transportation-related emissions. This proposition contains genuine merit for certain applications, particularly customized or on-demand items where traditional manufacturing and distribution prove inefficient.

Nevertheless, blanket claims about transportation emission reductions require contextual analysis. For mass-produced items, centralized conventional manufacturing with optimized logistics often proves more energy-efficient than distributed 3D printing, even accounting for transportation. The energy intensity per unit typically favors high-volume traditional manufacturing for standardized products, while additive manufacturing excels in low-volume, high-complexity, or customized applications.

Companies promoting localized 3D printing as universally superior from an emissions perspective oversimplify complex supply chain dynamics and engage in greenwashing when they fail to acknowledge these nuances.

📊 Certifications and Standards: Separating Signal from Noise

Third-party certifications and industry standards theoretically provide objective verification of environmental claims, offering consumers and businesses reliable benchmarks for evaluation. However, the proliferation of certifications—varying widely in rigor, scope, and credibility—creates its own navigation challenges.

Legitimate Certifications Worth Recognizing

Several established certifications carry genuine weight in validating environmental claims within the 3D printing space. ISO 14001 certification indicates that a company has implemented an environmental management system with defined policies, procedures, and improvement objectives, though it doesn’t certify specific product attributes.

Cradle to Cradle certification assesses products across multiple sustainability dimensions, including material health, material reutilization, renewable energy use, water stewardship, and social fairness. This comprehensive framework provides meaningful insight into a product’s overall environmental profile.

For specific materials, certifications like USDA BioPreferred (verifying bio-based content), TÜV Austria’s OK compost certification (validating compostability claims), or the Nordic Swan Ecolabel (covering multiple environmental criteria) offer credible third-party verification.

Red Flags in Certification Claims

Self-created “certifications” or vague references to “eco-standards” without naming specific certifying bodies signal potential greenwashing. Legitimate certifications come from independent organizations with transparent methodologies and public verification processes.

Companies displaying certification logos without providing certification numbers, dates, or links to verification also merit skepticism. Authentic certifications include traceable documentation that consumers can independently verify through the certifying organization’s database.

Beware of certifications that assess only narrow aspects while companies imply broader environmental superiority. A material certified as bio-based tells you about feedstock origin but nothing about energy consumption, toxicity, end-of-life options, or overall lifecycle impact.

💡 Asking the Right Questions: Consumer Due Diligence

Navigating greenwashing requires active consumer engagement and critical evaluation of environmental claims. Rather than accepting marketing assertions at face value, informed buyers ask probing questions and seek substantive answers.

Material Transparency Inquiries

When evaluating materials marketed as sustainable, request specific information about composition, sourcing, and end-of-life options. What percentage of the material derives from renewable or recycled sources? What are the remaining components? Where and how is the material produced? What specific conditions enable biodegradability or compostability, and are those conditions realistically accessible?

Companies genuinely committed to sustainability typically provide detailed answers with supporting documentation. Vague responses or reluctance to share specific data suggests potentially exaggerated claims.

Energy and Emissions Data

Request concrete energy consumption data for both printing operations and required post-processing. Ask whether the company has conducted lifecycle assessments comparing their additive manufacturing solution to conventional alternatives for your specific application. Have they quantified the carbon footprint across material production, printing, and end-of-life scenarios?

Legitimate sustainability leaders increasingly provide environmental product declarations (EPDs) containing standardized lifecycle assessment data verified by independent third parties. The absence of such documentation doesn’t necessarily indicate greenwashing—many smaller companies lack resources for formal EPDs—but the presence of verified EPDs strongly signals credible environmental commitment.

End-of-Life Reality Check

Perhaps no area invites more greenwashing than end-of-life messaging. Companies may emphasize theoretical recyclability while offering no practical recycling programs. They might tout biodegradability without clarifying the specific conditions required or accessibility of appropriate facilities.

Ask direct questions: Does the company operate a take-back or recycling program? If claiming recyclability, what specific recycling stream accepts the material, and how widely available is that infrastructure? If promoting compostability, which composting facilities accept the material, and how can consumers locate them?

🎯 Industry Responsibility and Moving Forward

Addressing greenwashing requires action from multiple stakeholders, with manufacturers and service providers bearing primary responsibility for honest communication. Industry associations can establish clearer standards and best practices for environmental claims, while regulators may need to strengthen enforcement of existing truth-in-advertising laws as they apply to sustainability assertions.

Best Practices for Ethical Environmental Communication

Companies genuinely pursuing sustainability should embrace transparency as a competitive advantage rather than viewing disclosure as risk. Provide specific, quantified environmental data with clear methodologies. Acknowledge limitations and trade-offs honestly rather than presenting misleadingly simplified narratives. Seek credible third-party verification for significant environmental claims.

Invest in legitimate lifecycle assessments that account for all stages from raw material extraction through manufacturing, use, and end-of-life. Make this data publicly accessible in standardized formats that enable meaningful comparisons.

Support industry-wide standards development that establishes consistent methodologies for measuring and reporting environmental metrics specific to additive manufacturing. Standardization enables consumers to make informed comparisons and rewards genuine environmental leadership.

The Path Toward Authentic Sustainability

The 3D printing industry stands at a crossroads. Additive manufacturing genuinely offers environmental advantages for specific applications, but realizing its sustainability potential requires moving beyond superficial green marketing toward substantive environmental performance improvements backed by transparent data.

Companies that embrace rigorous environmental assessment, honest communication about both benefits and limitations, and continuous improvement in measurable environmental metrics will ultimately build stronger brands and customer loyalty. Conversely, those relying on vague green claims and selective disclosure face increasing reputational risk as consumer awareness grows and regulatory scrutiny intensifies.

For the technology to fulfill its environmental promise, the industry must prioritize integrity over marketing convenience, substance over symbolism, and verifiable performance over aspirational rhetoric.

🌍 Empowering Informed Decision-Making

Ultimately, combating greenwashing empowers better decision-making throughout the 3D printing ecosystem. When consumers demand substantiated environmental claims and reject misleading marketing, they create market incentives for genuine sustainability innovation. When businesses conduct thorough due diligence on supplier environmental assertions, they build more resilient and responsible supply chains.

The environmental stakes are too high for complacency. Climate change, resource depletion, and plastic pollution demand authentic solutions, not merely green-tinted marketing narratives. Three-dimensional printing can contribute meaningfully to sustainable manufacturing transitions, but only if the industry commits to honest assessment and communication of its environmental profile.

By asking critical questions, demanding transparent data, seeking credible certifications, and maintaining healthy skepticism toward exaggerated claims, stakeholders can navigate the greenwashing landscape effectively. This vigilance not only protects individual interests but collectively drives the industry toward more authentic and impactful environmental responsibility.

The future of sustainable 3D printing depends not on perfect environmental solutions—which rarely exist—but on honest acknowledgment of trade-offs, continuous improvement based on rigorous data, and transparent communication that respects consumer intelligence. Printing with integrity means more than dimensional accuracy; it requires truthfulness in every claim and commitment to substantive environmental progress over superficial green positioning.

Toni Santos is a materials researcher and sustainable manufacturing specialist focusing on the development of next-generation biopolymer systems, renewable feedstock cultivation, and the practical innovations driving resource-efficient additive manufacturing. Through an interdisciplinary and science-driven approach, Toni investigates how natural organisms can be transformed into functional materials — across filament chemistry, bio-based composites, and closed-loop production systems. His work is grounded in a fascination with algae not only as lifeforms, but as carriers of industrial potential. From algae filament research to bio-resin development and durable low-energy prints, Toni uncovers the material and engineering pathways through which sustainable practices reshape the future of digital fabrication. With a background in material science and sustainable manufacturing, Toni blends polymer analysis with renewable biomass research to reveal how natural resources can be harnessed to reduce carbon footprint, improve durability, and enable circular production. As the creative mind behind Veltrynox, Toni curates biofilament innovations, low-impact printing methods, and material strategies that advance the ecological integration of 3D printing, biopolymers, and renewable manufacturing systems. His work is a tribute to: The renewable potential of Algae Filament Research and Cultivation The transformative chemistry of Bio-Resin Development and Biocomposites The engineering resilience of Durable Low-Energy Print Systems The sustainable future of Eco-Friendly 3D Printing and Green Manufacturing Whether you're a materials innovator, sustainability engineer, or curious explorer of renewable manufacturing, Toni invites you to discover the transformative power of bio-based materials — one layer, one filament, one sustainable print at a time.